It's Been Fun, 'Heated Rivalry'

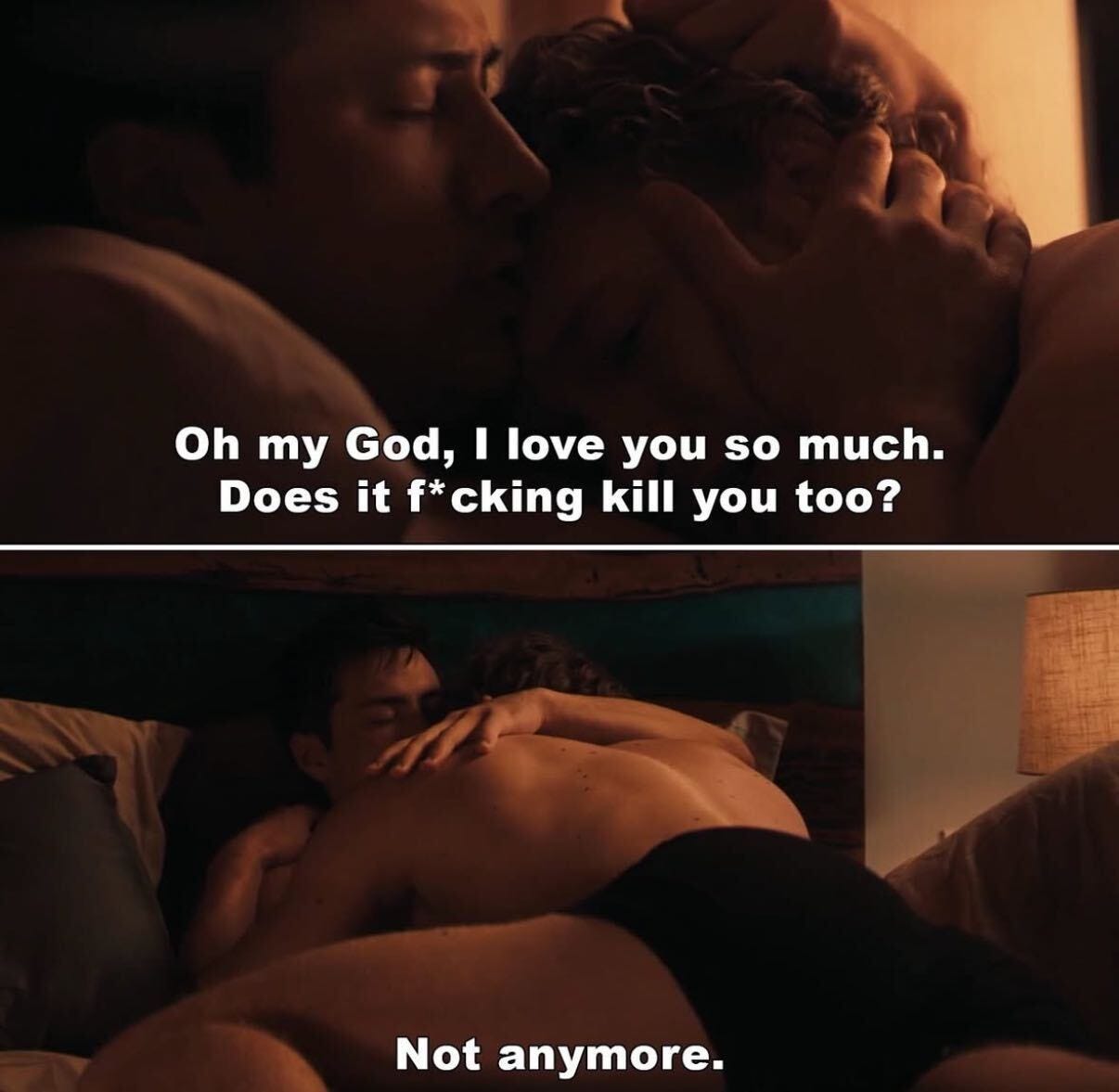

“I thought all we did anymore was hate things and find a f*cked-up joy in that. Then you came along.”

It was, if we’re being honest, a year of mid TV. And that’s okay. They can’t all be 2013 level. In a post-Golden Age of Television landscape, the emphasis has shifted to quantity over quality and thus we’re left with more of a buffet style than an artfully curated menu of offerings. We’re certainly not starved and good-even-great TV of course prevails, but I fear that our eye for quality diminishes when the surplus of bad-even-awful begins to pollute the form. And then came Heated Rivalry, a Canadian sports romance, crash landing on planet HBO at midnight on Thanksgiving. And over the course of the next five weeks, we’ve witnessed nothing short of a cultural phenomenon spreading its transfixing tentacles into a chokehold — the good kind.

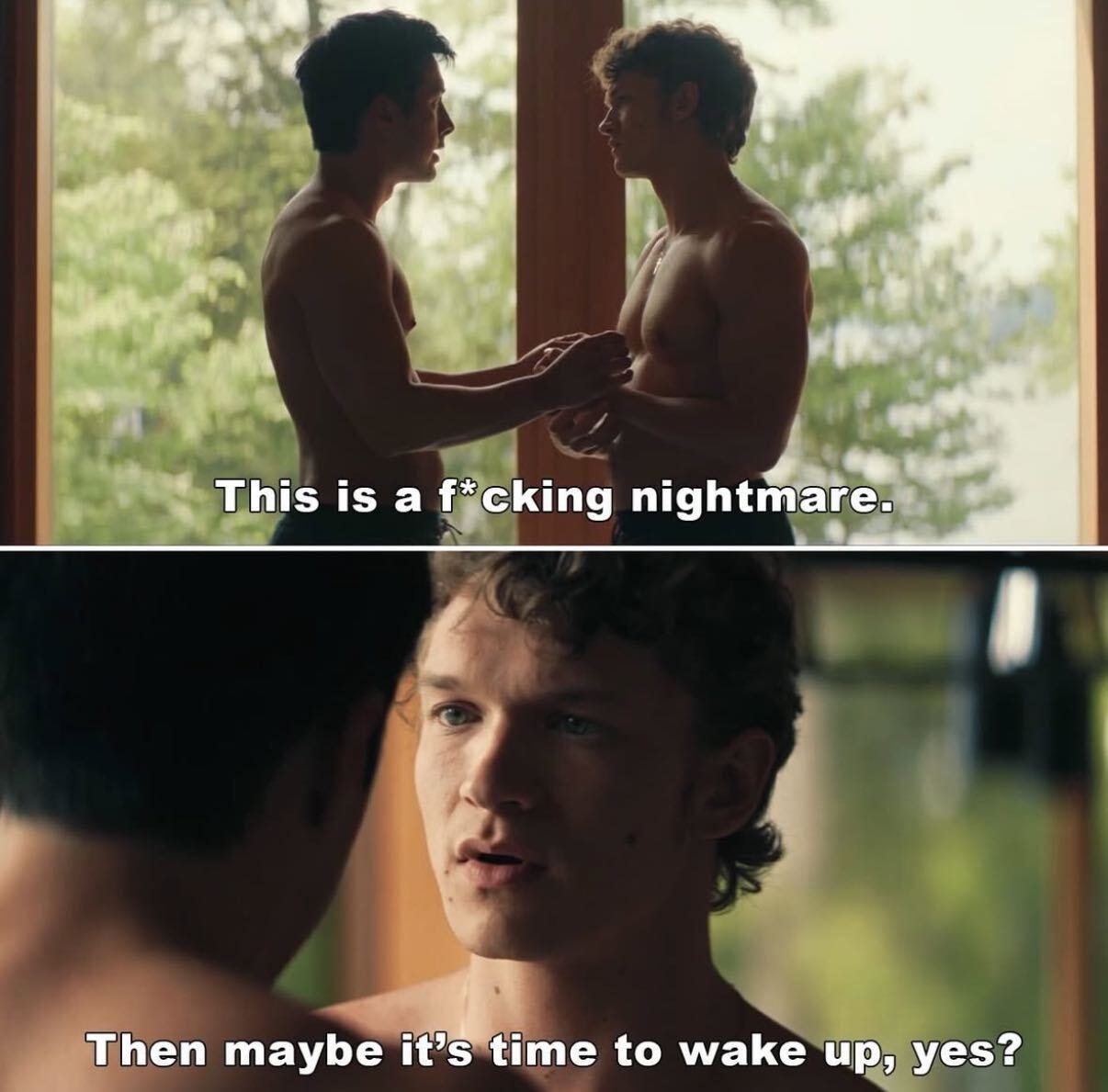

The alchemy is near perfect: Seemingly out of nowhere but scaffolded by a core, protective-yet-inviting literary fanbase eager to help propel the series to the frontlines; overtly sexy, downright horny content that seemed to rebuke recent headlines like “Gen Z is afraid of sex”; a charm offensive from the shows leads at time when the culture is desperate for the kind of charismatic stars that seem increasingly of yesteryear; and a masterful bait and switch of hockey smut slowly and methodically giving way to an earnest and passionate love story, the likes of which perhaps not seen at this scale of visibility since, well, it’s hard to really say! Every time I think of a comp (Normal People? Outlander? Bridgerton?) I’m left feeling more “sorta, kinda” than “yes, that one”! Perhaps time and space will tell (Season 2 has been announced but likely won’t make its way to us until 2027, as is the frustratingly modern pace of television production).

But perhaps most shocking of all, a finale that successfully landed the plane after a penultimate episode that rendered the Internet both able to lift a car and in a state that can only be described as Timothée Chalamet at the end of Call Me By Your Name. Episode 5 became the second highest-rated television episode ever on IMDb, earning a perfect 10/10 rating (it has now dropped to #16) and had many, I among them, shouting, “Emmy’s, now!” Could creator Jacob Tierney and co. deliver a finale that created closure for our newly beloveds, left the door open for another season and avoided prototypical clichés? As it turns out, of course he could (and for the record: I never doubted you, Jacob). As Richard Lawson wrote in his fantastic new newsletter, the finale is “sexy and sweet and surprisingly avoids the narrative pitfalls—the carefully orchestrated setbacks—I kind of thought had to eventually plague a show like this. (If, indeed, there has been a show like this before.)”

I could opine about all of the things that I loved about the show — the needle drops, the specificity of the shot coverage, Kip’s dad, Shane justifying making eight burgers for the two of them because “the recipe was for eight,” the police car driving by right after Ilya tells Shane that he wishes his father, a former cop, could have known him — and I could go on and on, but I want to take a moment to celebrate this fandom. “I love a big cultural moment like this,” I told Connor Storrie during our interview earlier this month.

“I love how exciting it is watching people have something to love. I need not tell you it’s a miserable world out there right now. There’s a lot of things to hate about the world, about society, maybe even about the entertainment industry. And what you are doing on this show and what this creative team is bringing forward is joy for a lot of people and that needs to be celebrated and taken seriously.”

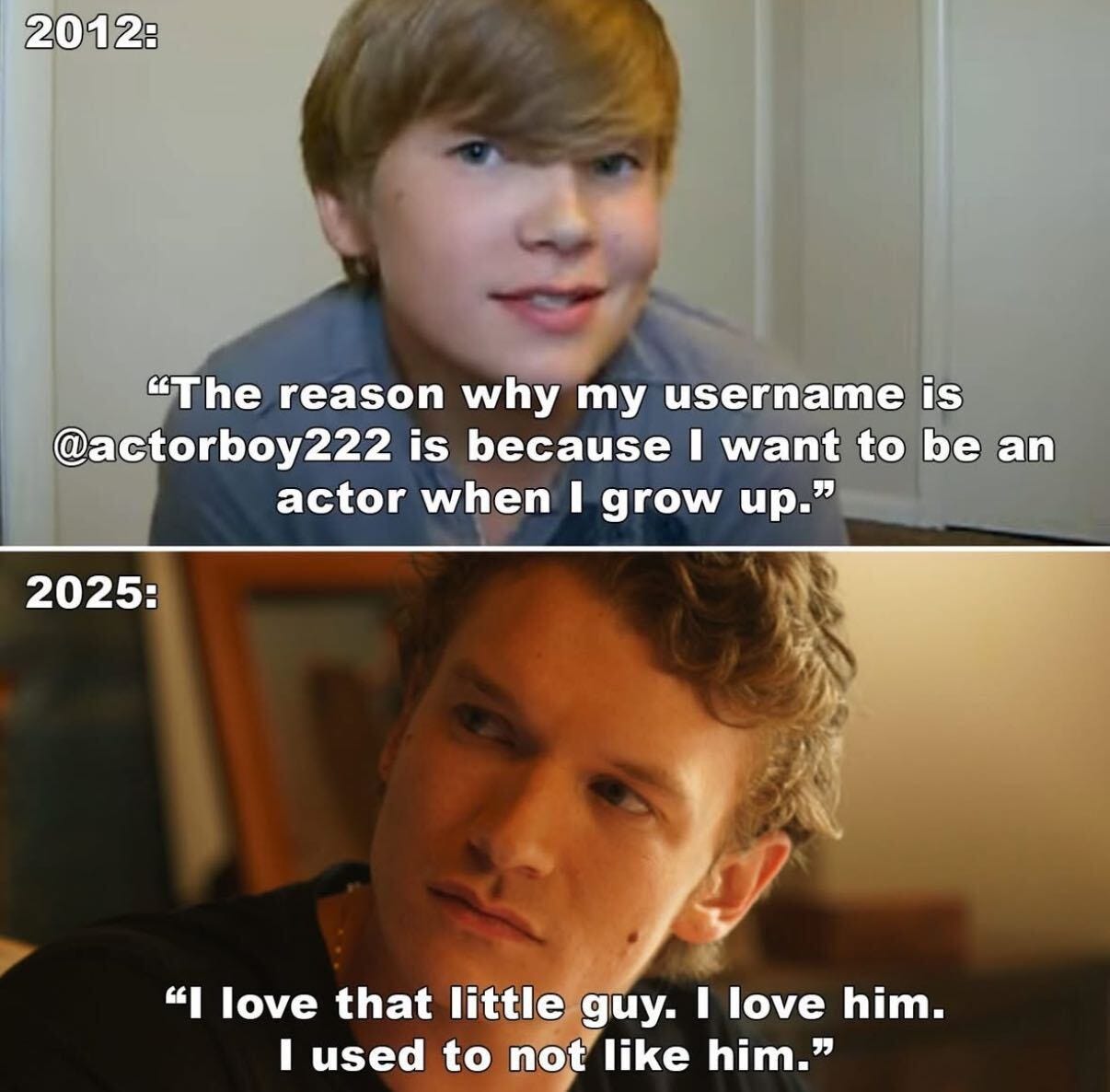

I think this show’s impact is so wide that the width of the frame begins to curve. I’ve heard people say that the show is healing for them, for their former selves or the selves that they buried deep down. And maybe that’s the story on screen or maybe it’s the tender and thoughtful way the creatives have spoken about the show’s more far-reaching impact. Storrie, for instance, showed love to his 12-year-old self, the “sissy boy in West Texas,” as he described it, noting that though he didn’t used to like him, he’s learned, in adulthood, to “love that little guy.”

And with that, I think the show has brought about an earnestness that the Internet has long rolled its collective eye at. “I’m never earnest on the world wide web…” actress Nadine Bhabha (who plays Elena on the show) remarked on Instagram in a post thanking fans.

I’ve noticed it even in myself and the discussions I’m having about this show, the way conversations about it morph into conversations about our proximity to it and then, in some instances, dissolve into conversations about our queer selves or our closeted selves or our self-hating selves or maybe an amalgam of all.

But what I think really cements this as a phenomenon — and really, we owe as much a thank you to HBO as we do to Crave — is how wide a net this show has cast. Rarely do we have a show that brings together this many demographics: fujoshis, gay men, hockey bros, etc. As a gay man myself, I’ve been surprised to see gay men’s acceptance (for the most part!) of something whose predecessors often invite sneers. Outside of the show being good, what’s that about? According to NPR’s Glen Weldon, the context matters.

“Yes, the men are hot. Yes, the sex is explicit. But context matters. This is a mainstream product. It’s not some of those, you know, alternate means I just mentioned. It means that gay men don’t have to pretend it doesn’t exist when we talk to our straight friends. We don’t have to restrict the conversation to our private-group chats. We can talk about this show with people outside our close-friend circles, and that’s what “mainstream” means. It means it’s more socially acceptable. I guarantee you, there are going to be some very weird conversations over Christmas dinner with the family this year about this show. Boundaries will be crossed.”

In that sense, this seemingly niche show breaking containment has created a big tent that the DNC should be taking note of as we approach the midterms. It has been that rare piece of art that creates conversation about itself and its existence within the broader culture. But it also has spawned so many conversations: “Can you believe how horny people are for this show?” “Are people just starved for sexually explicit content?” “Why is this show hotter than most of the porn being produced today?” “Will Hollywood start greenlighting more gay shit?” “Will romantic smut be taken more seriously?” “Wait, so there are non-toxic fandoms out there?” “So you can cast unknowns and still have a hit show?” “Wait, a hit show doesn’t need a $400M budget?” The list goes on and on.

The last month has been less hellish than any other of the year for me. Maybe you feel similarly. It’s been so lovely discovering this show, being in conversation with others who love it, laughing at the memes, swooning at the close-ups, being entranced by the influx of analysis from critics and superfans alike. I thought all we did anymore was hate things and find a fucked-up joy in that. I thought that was just how it goes. And I accepted that as a symptom of the times. What we needed to do, collectively, to get through it all.

I grew up a child of fandom. I wrote Sarah Michelle Gellar handwritten letters in my early teens, lying and telling her I’d watched Cruel Intentions even though I wasn’t yet allowed. I poured over the card catalogue at the library in search of books that could feed my appetite for the culture that gave me a sense of identity and meaning and made me feel infinitely less alone. Then it became message boards and the Internet made me feel part of something. Fandom changed for me from being in isolation to something that connected me to others. Like Buffy meeting Kendra in Season 2 and discovering she wasn’t the only Slayer.

Somewhere along the way, blame it on cynicism perhaps, fandom became more innate than purposeful, and lost in that was how much joy I derived from both loving something and finding others who love the thing just as deeply or more deeply or differently deeply or all of the above. I’ve loved how much Heated Rivalry has made me (and I wager others) feel a part of something at a time when isolation and loneliness are so corrosive. It’s been fun to collectively freak out over things like tuna melts and cottages and loons and Feist and watching a young man put on a suit ahead of having his first hook-up with another guy. It’s been fun to love something unironically, unashamedly and unpretentiously.

It’s been fun, Heated Rivalry. Come back soon, won’t you?

“joy derived from both loving something and finding others who love the thing just as deeply or more deeply or differently deeply” extremely good definition of fandom, thank you - the “differently deeply” is so important!!!!!